‘I couldn’t say my own name without stuttering or stammering.’

Christie Toney was 21 years old by the time she could say her own name out loud in front of a stranger without stammering or stuttering.

Two years ago, after graduating from University College Dublin with a master’s degree in biopharmaceutical engineering, Toney felt her speech disorder was holding her back in job interviews, so she enrolled in a course called the McGuire Programme.

The intensive course gives people control over their stammer in three to four days by using a new way of breathing and overcoming the fear of stammering. The methods deployed during the courses, which are typically led by former-members-turned-coaches, can seem a little unorthodox; the first day Toney attended her course at a hotel in Newry, Co Down, she was asked to stand in front of the other participants and answer questions while her speech was being recorded.

On the final day, Toney and the other students were taken out in small groups to the streets of Newry and asked to “make 100 contacts in three hours”, for example by asking people for directions. At the end of that session, Toney took her turn at standing on a soapbox in a shopping centre and speaking out loud for two minutes.

“Those three days changed my life,” says Toney, who now works at a pharma company. “After doing the programme, I realised that all of those years of negative experiences associated with my stuttering had really shaped my perception of myself. My speech had always been a burden to me, something I’d always been ashamed of.

“I had to make a conscious decision not to allow my stutter to define my life any more. But each day is an uphill battle.”

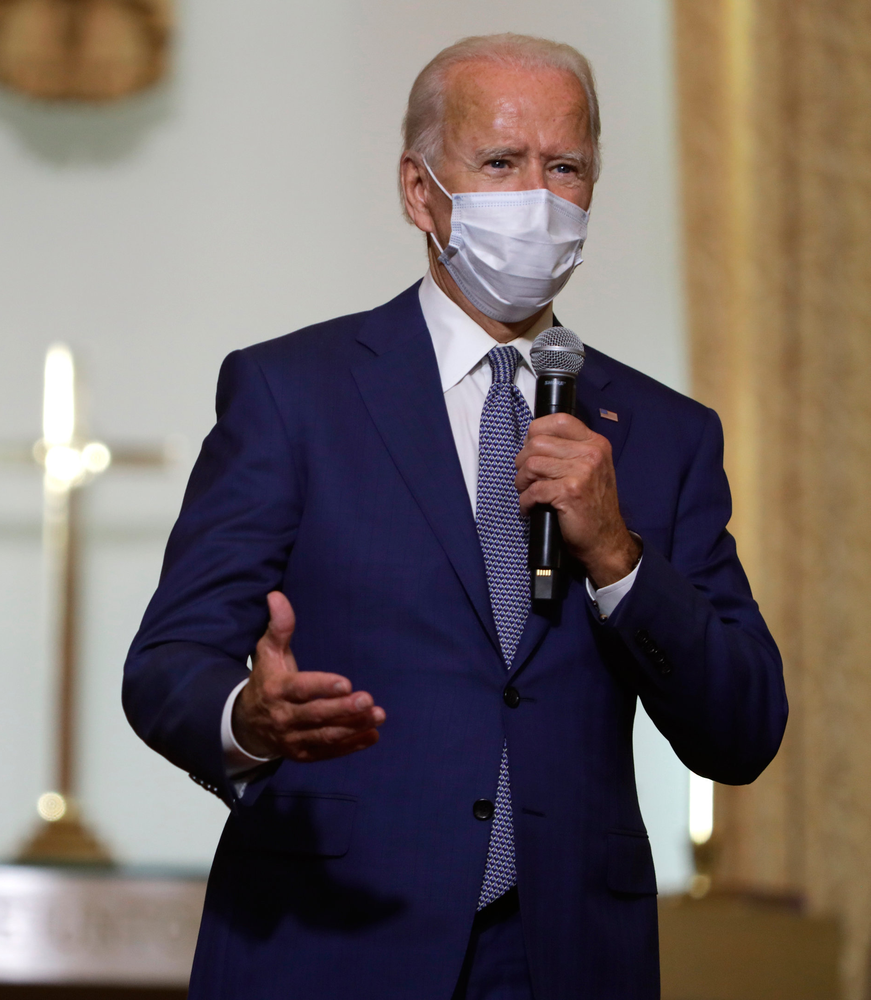

According to the stereotype, the Irish have the gift of the gab. But many of us have difficulty getting the words out: about 1pc of the population – or almost 50,000 people – stutter, according to the Irish Stammering Association (ISA). The speech disorder disproportionately affects males, with estimates that about four times as many males than females have a stammer. One of the most high-profile men to highlight the condition recently has been Joe Biden.

Getty Images

While on the campaign trail, the US presidential candidate has recalled his childhood struggle with a stammer, including how he recited Irish poetry in front of a mirror as a teenager to try to assert control over his speech and how his mother confronted a teacher at his school who had humiliated him when he was reading aloud from a book.

When Biden was US vice-president and took his family to Ireland in 2016, he spoke to a member of the ISA about how he overcame stammering, says David Heney, who is chairman of the association.

Heney himself became self-conscious about speaking in the workplace earlier in his career because of his overt stammer, which was accompanied by secondary behaviours such as tensing up and tapping his fingers. In 2007, he took part in a week-long HSE group residential therapy programme at a hotel, after realising that he was blaming a relationship breakdown on his speech.

“I used to blame a lot of things on my stammering, thinking ‘oh, I can’t do this’ and using it as an excuse,” Heney says.

Before the HSE programme, which was subjected to austerity cuts during the recession, Heney had never met other people who stammered.

“That’s probably why speech therapy hadn’t worked for me before,” he says. “But this time, it was about becoming accepting of your stammering it rather than curing it.”

There is no known cause or cure for stammering. Some research has indicated that neurological problems can crystalise the genetics that predispose a person to stammer. That impact, Heney says, can then be exacerbated by fears that people build over the years of certain situations, such as of a job interview or meetings.

“There have been some drug trials over the years but there haven’t been any major breakthroughs and they tend to treat stammering in relation to anxiety,” he says. “Speaking to academics and looking at research, the greatest impact seems to be acceptance of stammering and extending your comfort zone; if you start avoiding people and situations, you end up creating fears.”

When his older brother Edward VIII abdicated the British throne in 1936, King George VI was unexpectedly thrown into the role and feared the stammer he had struggled with since childhood would prevent him from giving public speeches. He overcame the obstacle after being treated by Australian speech therapist Lionel Logue, as depicted in the 2010 film The King’s Speech. Other well-known figures who have a stammer include the actor Emily Blunt, novelist Colm Tóibín, and the former Labour party politician and MEP Proinsias De Rossa.

It was the latter who resonated most with Nora Trench Bowles. She remembers growing up hearing De Rossa speaking with a stammer and “communicating clearly” in the media.

“It makes me want to start crying even thinking about it now,” says Bowles, who now works in the university sector and is a voluntary member of the ISA’s board.

“I stammered for a long as I can remember and I think I always will stammer. For most of my life, I could count on one hand the number of people I even said the word ‘stammer’ to because of the shame and the fear tied up in it. What has changed in recent years is becoming more open about my stammer.

“I imagine there is a perception that people who stammer are quiet or were horribly bullied. I can’t say that either of those who are true: I’m usually the loudest one in the room and I enjoyed school.

“I do have a standout memory of that one time someone in school said something mean to me about my stammer, but the impact is perhaps is more internal. It’s about the debating societies I didn’t join and the school plays I didn’t take part in because, at that age, I didn’t think it was possible to have a stammer and do those things; the idea of a stammer being heard that publicly was too much to bear. It hasn’t changed completely, because there are still days I avoid certain words or situations.

“There are a few celebrities now who talk about their experiences about having a stammer, Joe Biden is the big one of the moment, and Emily Blunt has done a few interviews.

“But I would like to hear more people on the radio and see more people on TV stammering and not necessarily talking about their stammering but talking about a whole range of topics. It comes down to representation.

“When stammering comes up in popular culture, like in the media or on TV or in films, it’s either as the butt of a joke or a sign of someone sinister. I saw a presentation once where quite often someone who plays a criminal on TV is stammering to denote that they are unhinged.

“As a society, we have come a long way towards tolerance in lots of ways, but that hasn’t caught up to people who stammer.”

The ISA Walk and Talk event, a social gathering for people who stammer and their friends and families, will be held the banks of the Royal Canal in Dublin on September 20.